Every medical intervention comes with trade-offs. When prescribing a medication, clinicians help patients weigh its potential benefits against its possible side effects and potential risk of adverse reactions (the “non-intended effects” of medications).

Often, the benefits outweigh the risks. This is why even the severe side effects of cancer treatments are tolerated compared to the potential upside of the therapy. Exogenous hormones, whether used as contraception or as menopause hormone therapy (MHT/HRT), are no different. They can bring life-changing benefits, but they also carry potential risks.

One of the most persistent, and understandably emotional, concerns around hormone use is cancer risk. Headlines tend to simplify this relationship into binaries: “The pill causes breast cancer.” As per usual in medicine, the reality is more nuanced. Exogenous hormones may increase the risk of certain cancers, but lower the risk of others, and the individual context matters enormously.

.jpg)

Initially, we planned to explore both contraception and hormone therapy in one piece, but decided that each deserves its own careful unpacking. So in this article, we will focus on hormonal contraception.

And one more disclaimer: why focus on contraception when the spotlight right now seems fixed on menopause hormone therapy? Because hormonal contraception is not just a tool for preventing pregnancy. It can be a valuable option in perimenopause. It can be a hormonal treatment for patients with PCOS, endometriosis, and PMS. It can even serve as a performance and health tool for female athletes with challenging menstrual cycles. So we look at and evaluate it for what it is - a form of exogenous hormones.

So let’s start with aligning on the most popular topic - contraception and breast cancer.

Hormonal contraception & increased breast cancer risk

Hormonal contraceptives, including combined oral contraceptives (also referred to as COCs, CHCs) and progestin-only methods such as levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices (LNG-IUDs), implants, and injections (DMPA), are associated with an increased risk of breast cancer (~20-30%) during current or recent use, which diminishes after discontinuation. Most studies show that the increased risk decreases within 5–10 years after discontinuation, with no significant excess risk after 10 years.

Risk Overview

Let’s start with the studies and exact findings.

A 2017 study of 1.8 million Danish women found a relative risk (RR) of 1.20 (95% CI 1.14-1.26) for current or recent users of hormonal contraception compared to never-users [1]. A 2023 UK study reported odds ratios (ORs) of 1.23 (95% CI 1.14-1.32) for combined contraceptives and 1.26 (95% CI 1.16-1.37) for oral progestin-only methods [2]. The risk increases with duration of use, from an RR of 1.09 (95% CI 0.96-1.23) for less than 1 year to 1.38 (95% CI 1.26-1.51) for over 10 years [1]. The elevated risk returns to baseline within 10 years of discontinuation, with no increased risk for prior users of less than 5 years after this period [3]. The 2023 UK study estimated a 15-year absolute excess risk of 8 per 100,000 users aged 16-20 (incidence increasing from 0.084% to 0.093%) and 265 per 100,000 users aged 35-39 (from 2.0% to 2.2%) [2]. A meta-analysis from 2023 showed a statistically significantly higher breast cancer risk in every user of hormonal contraception compared to non-users (pooled OR = 1.33, 95% CI, 1.19 to 1.49; I2 = 82%; p < 0.01%) [9].

So what does it mean for you?

To understand this data, it’s important to note that the overall average risk of a woman in the United States developing breast cancer sometime in her life is about 13%. This means there is a 1 in 8 chance she will develop breast cancer [10]. So, if your average risk is 13%, if hormonal contraception increases the relative risk by 20% (RR = 1.20), then:

13% × 1.20 = 15.6% → your average lifetime risk would increase from 13% to about 15.6%.

The absolute risk remains small, particularly for younger women. Breast cancer is rare at 20, but commoner at 40+, so the same relative risk (say 20–30%) translates into a much larger absolute risk in older women.

For younger women, the actual increase is small because breast cancer is rare before age 40:

- For women 16-20: Out of 100,000 users, only about 8 additional cases would occur over 15 years

- For women 35-39: About 265 additional cases per 100,000 users over 15 years [2].

In absolute terms, the increased breast cancer risk translates to a small increase in individual risk, but it’s relevant when we look at population-wide impact.

Mechanisms behind increased breast cancer risk

The exact biological mechanisms linking hormonal contraceptives to breast cancer are not fully understood. Most evidence points to the effects of exogenous hormones, particularly synthetic progestins, and to a lesser extent estrogen, on breast tissue.

Synthetic progestins are thought to be the main drivers of risk. Unlike natural progesterone, they can bind not only to progesterone receptors (PR, especially PR-B), but also to estrogen receptors (ER) and glucocorticoid receptors (GR), promoting proliferative pathways in breast tissue.

(Bear with us as we’re not oncology researchers, but here’s what we found in the literature on the topic. This section is for the geeks in the room!)

Proposed mechanisms:

- Receptor binding and proliferation: Progestins and estrogens stimulate the proliferation of breast epithelial cells, raising the chance of DNA replication errors and mutations. Synthetic progestins (especially 19-nortestosterone derivatives like norethindrone, levonorgestrel) can act as ER agonists at pharmacological doses, driving proliferation in ER-positive cell lines (MCF7, T47D) [4]. PR-B activation also induces RANKL, a key mediator of progesterone-driven proliferation [5]. Medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), a progesterone-derived progestin, shows high GR affinity, adding another proliferative pathway [5].

- Off-Target Effects: Synthetic progestins exhibit off-target effects, including androgenic (19-nortestosterone derivatives) and glucocorticoid (MPA) activities, which may influence cell survival. For instance, MPA increases cell viability in cells overexpressing PGRMC1, a membrane-associated progesterone receptor linked to antiapoptotic effects in breast cancer [6].

- Synergy with Estrogen: In combined hormonal contraceptives, estrogen synergizes with synthetic progestins to amplify breast cell proliferation. A French study found that estrogen plus synthetic progestins increased breast cancer risk (OR 1.57-3.35), while estrogen plus micronized natural progesterone did not (OR 0.80) [7].

- Pharmacokinetics: Synthetic progestins like MPA have high bioavailability (>90%) and long half-lives (~22 hours), leading to sustained receptor activation [5].

Interestingly, timing seems to matter too. Bonfiglio et al. concluded that the timing of the onset of hormonal exposure throughout a woman’s lifespan is probably the definitive risk factor for subsequent cancer development, as breast cells are most susceptible and vulnerable to carcinogens during puberty, pregnancy, and the years before a first full-term pregnancy [11].

💡 Takeaway: Hormonal contraceptives, especially those containing synthetic progestins, can attach to multiple hormone receptors in breast tissue, activate those receptors and pathways that stimulate breast cells to divide more often. The more cells divide, the greater the chance of errors in DNA replication, which can, over time, increase the risk of cancer.

Hormonal contraception & increased cervical cancer risk

Hormonal contraception, especially when used for ≥5 years, increases cervical cancer risk by ~60% (RR 1.6, 95% CI 1.3–2.0), primarily due to enhanced HPV persistence. This risk is not fully explained by increased sexual activity, though higher HPV exposure from more partners may contribute. Risk returns to baseline ~10 years after stopping. However, super important to note that 99.8% cervical cancer cases are preventable. The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine provides strong protection against cervical cancer caused by vaccine-covered HPV types, regardless of hormonal contraceptive use. Regular cervical screening also significantly reduces the risk [16].

Variation by types and formulations

Interestingly, so far, studies suggest that the increase in breast cancer risk is similar across contraceptive methods - whether combined hormonal contraceptive (CHC) pills, rings, or patches, or progestin-only options like implants, levonorgestrel (LNG) IUDs, or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA). This was somewhat unexpected, since lower-dose or locally acting methods (like the LNG IUD) were thought to carry less risk.

Emerging laboratory and mechanistic data suggest that it may be the specific progestin formulation, rather than the delivery route or dose, that matters most. For example, researchers are suggesting that androgenic progestins (e.g., levonorgestrel, desogestrel) can stimulate breast cell proliferation more strongly than anti-androgenic types. But so far, clinical evidence confirming those formulation differences in cancer risk among contraceptive users is lacking.

In contrast, menopause hormone therapy (MHT/HRT) data show clearer variation. Studies indicate that synthetic progestins (e.g., norethisterone, medroxyprogesterone acetate) are associated with higher breast cancer risk compared with natural micronized progesterone. The French study reported relative risks ranging from 1.16 to 1.69 for different progestins combined with estrogen, with 19-nortestosterone derivatives showing higher estrogenic activity [7]. MPA’s risk may stem from GR binding, while levonorgestrel’s risk is linked to ER activation [4].

Taken together, these findings underscore the need for more research into how specific progestins, not just the hormone route or dose, influence breast cancer risk.

The protective effects of hormonal contraception

A topic less likely to be highlighted on social media, but hormonal contraception appears to protect against several cancers. Studies show that women who have ever used hormonal contraception have a lower risk of developing certain cancers compared with those who have never used it.

Hormonal contraception users had a lower chance of developing [12]:

- Colorectal cancer (about 20% lower risk; IRR, 0.81; 99% CI, 0.66–0.99)

- Endometrial (womb) cancer (about 34% lower risk; IRR, 0.66; 99% CI, 0.48–0.89)

- Ovarian cancer (on average, about 33% lower risk; IRR, 0.67; 99% CI, 0.50–0.89, but can increase to 50% reduction after 10-15 years of use).

- Cancers of the lymphatic and blood systems (about 26% lower risk, IRR, 0.74; 99% CI, 0.58–0.94)

Unlike breast cancer risk, which returns to baseline a few years after stopping hormonal contraception, these protective effects appear to persist for many years after discontinuation.

Why does it matter to include this side of the equation in the conversation? Prognosis differs significantly between these cancers. Prognosis for breast cancer has improved dramatically, with ~85% of patients living 5 years or more after diagnosis, especially when caught early [13]. Endometrial cancer has similar 5-year survival rates (~85%) [14]. Colorectal cancer and ovarian cancer, in contrast, often go undetected until later stages, with poorer survival (~67% and ~45% at 5 years, respectively).

This means that the risk reduction from hormonal contraception may be particularly meaningful for cancers that are harder to detect early and have worse outcomes.

Proposed mechanisms

The protective mechanisms of hormonal contraceptives against these cancers are not fully understood, but several plausible biological explanations are supported by research [15]:

- Suppression of ovulation: Combined hormonal contraceptives suppress ovulation, reducing the number of times the ovarian epithelium is disrupted and repaired, which is thought to lower the risk of DNA replication errors and malignant transformation. Fewer ovulatory cycles mean less opportunity for DNA damage and malignant transformation in cells. Progestin-only methods can offer a similar risk reduction when they suppress ovulation (especially DMPA and higher dose LNG IUD).

- Progestin effect: The progestin component counteracts estrogen-driven proliferation in the endometrium, reducing the risk of endometrial hyperplasia and subsequent cancer.

- Reduced gonadotropin levels: Lower levels of LH and FSH result in less stimulation of the ovaries, further reducing risk.

- Lowering the levels of bile acids in the blood for women taking oral conjugated estrogens (colorectal cancer).

💡 In short: Hormonal contraceptives reduce cancer risk by suppressing ovulation, stabilizing the endometrium, and lowering hormone signals that would otherwise drive cell growth. Fewer cycles and less proliferation = fewer chances for DNA errors and malignant changes.

Research limitations to keep in mind

Whether we talk about the increased or decreased risk of cancer due to contraception, it’s important to keep in mind that nearly all the research on the link between hormonal contraceptives and cancer risk comes from observational studies. This includes large prospective cohort studies and population-based case–control studies. Data from observational studies cannot definitively establish or prove that an exposure (in this case, hormonal contraceptives) causes or prevents cancer. That’s because women who choose to use contraceptives may differ in important ways from those who don’t, and those differences, not the contraceptives themselves, might partly explain the variation in cancer risk.

That said, the fact that many independent studies have found consistent patterns makes the evidence convincing, even if it isn’t definitive. [16]

Genetic and Individual Factors

Cancer risk is not the same for everyone. Genetic predispositions and personal circumstances can significantly influence how hormonal contraceptives affect risk.

A 2024 study found that BRCA1 mutation carriers using hormonal contraceptives had a 29% increased breast cancer risk, with a 3% risk increase per year of use [8]. Data for BRCA2 carriers were inconclusive.

Beyond genetics, lifestyle factors like obesity and alcohol consumption, both of which independently raise cancer risk, can add to the equation and should be factored into individual risk assessments.

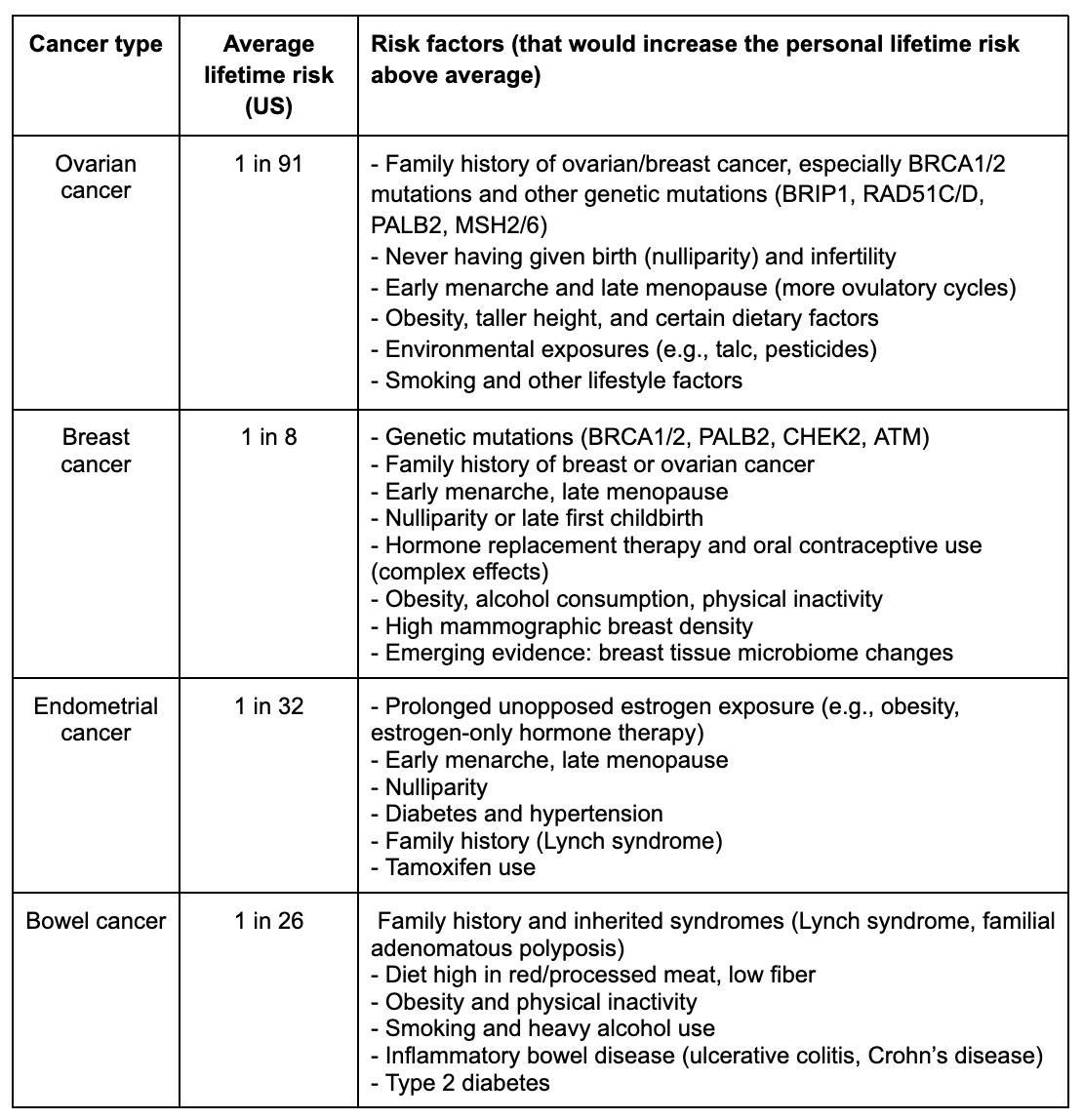

This is key. Remember: the average lifetime risk of breast cancer is about 13%. But your personal risk may be higher or lower depending on your genetics, family history, lifestyle, and reproductive history (such as age at menarche or menopause). Hormonal contraception and therapies intersect with all of these variables.

💡 People on the same hormonal contraceptive may face very different risks. A person with a genetic predisposition (e.g., BRCA1) could see their risk rise faster with contraceptive use. A person without that mutation but with obesity or high alcohol intake may already carry a higher baseline risk. A person starting hormonal contraception at a younger age may face a different risk profile than someone starting after pregnancy or later in life.

Context matters too

Cancer is a subject many of us would rather avoid, but when making decisions about hormones, being informed is crucial. Risk isn’t one-size-fits-all. Some cancers are relatively rare but dangerous (e.g., ovarian cancer), others are common but have a better prognosis (e.g., breast cancer, when detected early). As discussed, your personal baseline risk can be higher or lower than average depending on genetics, family history, lifestyle, and medical conditions.

For example, an increase in breast cancer risk may feel unacceptable to someone with a strong family history, while someone with no known risk factors might decide the protective benefits against ovarian or endometrial cancer outweigh the modest breast cancer risk.

Here’s a snapshot of average US lifetime risks and key risk factors that can shift those numbers up [17]. It’s not here to overwhelm you with numbers but to illustrate an important point: the average person’s risk is probably not your exact individual risk:

Conclusions: How do we navigate the nuance?

So how do we make sense of all this? Yes, hormonal contraception can increase the risk of breast cancer and cervical cancer. It’s an understandable concern and needs to be taken into account when making a decision/prescription.

What’s often overlooked is that hormonal contraception also reduces the risk of several other cancers, including ovarian, endometrial, and colorectal cancers, many of which have poorer prognoses than breast cancer because they are harder to detect early and lack effective screening tools.

That nuance matters. Decisions about contraception shouldn’t be made in isolation, but through a personalized risk–benefit assessment.

For patients:

- Know your baseline. Start with tools like the Tyrer–Cuzick model for breast cancer, map out your family history, and consider genetic testing where appropriate. Ideally, find a clinician who will help you order the right tests and help you understand your baseline cancer risk.

- Reduce cancer risk with modifiable factors. Genetics and family history can’t be changed, but diet, smoking, alcohol, and exercise are within your control, and they have a significant impact on overall cancer risk.

- Clarify your priorities. Medications come with trade-offs. Is pregnancy prevention your main goal? Cycle control? Symptom relief? Cancer prevention? All of them? All are valid, and they all impact how you and your clinician weigh the risks and benefits of using hormonal contraception.

For clinicians:

- Help them understand their personal risk and benefit ratio. Skip the one-size-fits-all approach. Factor in their family history, goals, genetics, lifestyle, and comorbidities.

- Communicate with clarity and compassion. Patients need evidence and education, not fear.

- Stay updated. The data is evolving. Recent research is beginning to distinguish between different progestins, hormone regimens, routes of administration, and durations of use. As our understanding grows, so too should our guidance.

When a patient asks, “Does hormonal birth control increase my risk of cancer?” the most honest answer is: “Yes. But the overall picture is more complex. It raises breast cancer risk while lowering the risk of other cancers. Your individual risk depends on your genes, lifestyle, and medical history, and the right choice is the one that balances your risks with potential benefits and your goals.”

Written with Dr. Paulina Cecula

References:

- Mørch LS, Skovlund CW, Hannaford PC, et al. Contemporary Hormonal Contraception and the Risk of Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2228-2239. Link

- Pirie K, et al. Combined and progestagen-only hormonal contraceptives and breast cancer risk: A UK nested case–control study and meta-analysis. PLOS Med. 2023;20(3):e1004188. Link

- National Cancer Institute. Oral Contraceptives and Cancer Risk. Accessed May 19, 2025. Link

- Schoonen WG, et al. Synthetic progestins induce proliferation of breast tumor cell lines via the progesterone or estrogen receptor. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1994;102(1-2):45-52. Link

- Brisken C, Scabia V. Progesterone and Breast Cancer. Endocr Rev. 2020;41(2):320-344. Link

- Neubauer H, et al. New insight on a possible mechanism of progestogens in terms of breast cancer risk. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2013;14(2):59-66. Link

- Fournier A, et al. HRT and breast cancer risk - progesterone vs. progestins. BMJ. 2019;367:l5928. Link

- Phillips KA, et al. Hormonal Contraception and Breast Cancer Risk for Carriers of Germline Mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(10):1121-1130. Link

- Torres-de la Roche LA, Acevedo-Mesa A, Lizarazo IL, Devassy R, Becker S, Krentel H, De Wilde RL. Hormonal Contraception and the Risk of Breast Cancer in Women of Reproductive Age: A Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Nov 28;15(23):5624. doi: 10.3390/cancers15235624. PMID: 38067328; PMCID: PMC10705112. [Link]

- American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2022–2024. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, 2022. Link

- Bonfiglio R., Di Pietro M.L. The Impact of Oral Contraceptive Use on Breast Cancer Risk: State of the Art and Future Perspectives in the Era of 4P Medicine. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021;72:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2020.10.008. [Link]

- Iversen L, Sivasubramaniam S, Lee AJ, Fielding S, Hannaford PC. Lifetime cancer risk and combined oral contraceptives: the Royal College of General Practitioners’ Oral Contraception Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Jun;216(6):580.e1–580.e9. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2017.02.002. [Link]

- Cancer Research UK. Breast cancer survival statistics. [link]

- American Cancer Society. Endometrial Cancer Survival Rates [Link]

- Abusal F, Aladwan M, Alomari Y, Obeidat S, Abuwardeh S, AlDahdouh H, Al-Shami Q, Odat Q. Oral contraceptives and colorectal cancer risk - A meta-analysis and systematic review. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022 Oct 3;83:104254. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.104254. PMID: 36389202; PMCID: PMC9661645. [Link]

- National Cancer Institute. NIH. Oral Contraceptives and Cancer Risk Fact Sheet. National Cancer Institute; 2022. [Link]

- American Cancer Society. (2025). Cancer Facts & Figures 2025. American Cancer Society. Retrieved September 7, 2025 [Link]

.jpg)

.jpg)