The internet is divided. Your doctor might be uncertain. And that new heart failure study has everyone second-guessing.

Here's why melatonin isn't a simple yes-or-no question—and how to think through it for yourself.

Some say it's a harmless natural hormone that supports sleep and longevity. Others point to concerning data about cardiac risks and question why we're casually taking a hormone every night. Biohackers swear by 50-100 mg doses for anti-aging. Sleep specialists rarely recommend more than 3 mg and often suggest stopping after a few weeks.

Who's right?

As a physician who's spent years translating longevity research, I'll tell you what I tell my patients: The answer is almost never universal. It depends on your specific context—and that requires understanding what we actually know, what we don't, and how to weigh risks and benefits for your particular situation.

Let's break it down.

The Problem With Treating Melatonin as a Harmless Supplement

Here's where the confusion starts: Melatonin is available over-the-counter, so we treat it casually. But unlike vitamin D (where deficiency is common and supplementation more clearly beneficial), melatonin is a hormone your body produces every night in precise amounts—and by supplementing, we're overriding that system.

The regulatory blind spot: In the U.S., melatonin is classified as a dietary supplement, not a drug. That means:

- No standardized dosing guidelines

- Minimal long-term safety monitoring

- Highly variable quality between brands (some studies found actual content ranging from 83% to 478% of labeled dose)

- No requirement for warning labels about prolonged use

Compare this to Europe, where melatonin is prescription-only in many countries and capped at 2 mg for most uses. That regulatory caution isn't arbitrary—it reflects uncertainty about long-term effects.

The cultural moment we're in: Melatonin use among U.S. adults has increased fivefold since 1999. We're now in this massive uncontrolled experiment where millions of people are taking it nightly, often at escalating doses, for years or decades. And we're only just starting to see what might happen as a result.

The Chronic Sleep Use Case: Why I'm Increasingly Skeptical

Let's start with the most common reason people reach for melatonin: trouble sleeping.

What the Research Actually Shows for Sleep

The evidence for melatonin's sleep benefits is real but modest:

- Reduces sleep onset latency by 7-10 minutes

- Increases total sleep time by 8-15 minutes

- Most effective for circadian rhythm disorders (jet lag, shift work, delayed sleep phase)

Important context: These numbers come from short-term studies—typically 4-12 weeks. We have very little high-quality data on what happens with nightly use for months or years.

The Tolerance Problem Nobody Talks About Enough

Here's the pattern I see clinically that concerns me:

Week 1-4: Patient starts with 1-3 mg. It helps a bit.

Month 2-3: The effect seems to diminish. They increase to 5 mg.

Month 6: Now they're taking 10 mg and it's "not working like it used to."

Year 2: They're trying 15-20 mg or adding other supplements.

While the research on melatonin tolerance is mixed, clinical experience suggests many people develop some degree of habituation. Your body has receptor systems (MT1 and MT2) that respond to melatonin—and like many receptor systems, they can downregulate with chronic stimulation.

The result? People end up taking higher and higher doses to chase the same effect. And now we're seeing preliminary data suggesting those higher, prolonged doses may carry cardiovascular risks.

What's Really Driving Your Insomnia?

This is the crucial question most people skip. Melatonin helps with circadian timing—it's your body's "it's nighttime" signal. But if your insomnia stems from:

- Anxiety or racing thoughts

- Sleep apnea

- Restless leg syndrome

- Chronic pain

- Poor sleep hygiene

- Screen time before bed

- Irregular sleep schedule

...then you're addressing the wrong problem. Melatonin becomes a band-aid that prevents you from finding and fixing the actual cause.

The cognitive behavioral therapy data: Multiple meta-analyses show CBT for insomnia (CBT-I) is more effective than melatonin for chronic sleep issues, and the benefits persist after treatment ends. A 2022 systematic review found CBT-I improves sleep quality by 0.8-1.2 standard deviations—meaningfully better than the 0.3-0.5 SD improvements seen with melatonin.

My Take on Chronic Melatonin for Sleep

I don't love it. Here's why:

- The tolerance trajectory: Many people escalate doses over time, which wasn't what the original studies supported

- The masking effect: It may prevent people from addressing root causes of poor sleep

- The emerging safety signals: While not definitive, the 2025 cardiovascular data is concerning enough that I'm not comfortable recommending years of nightly use, especially in older adults

- The opportunity cost: Time spent taking escalating melatonin doses is time not spent on interventions with stronger evidence (sleep hygiene, CBT-I, treating underlying conditions)

Where I do think it makes sense for sleep:

- Short-term use (2-4 weeks) to reset sleep patterns

- Intermittent use for jet lag or shift work

- Specific circadian disorders like delayed sleep phase syndrome

- As part of a broader sleep optimization plan, not as the sole intervention

Bottom line for chronic insomnia: If you've been taking melatonin nightly for more than 3-6 months and you're still having sleep problems, it's time to dig deeper. The melatonin isn't solving your issue.

The High-Dose Advocates: What They're Actually Saying (And Why)

Now let's talk about the other side—because dismissing high-dose melatonin users as reckless biohackers misses some genuinely interesting science.

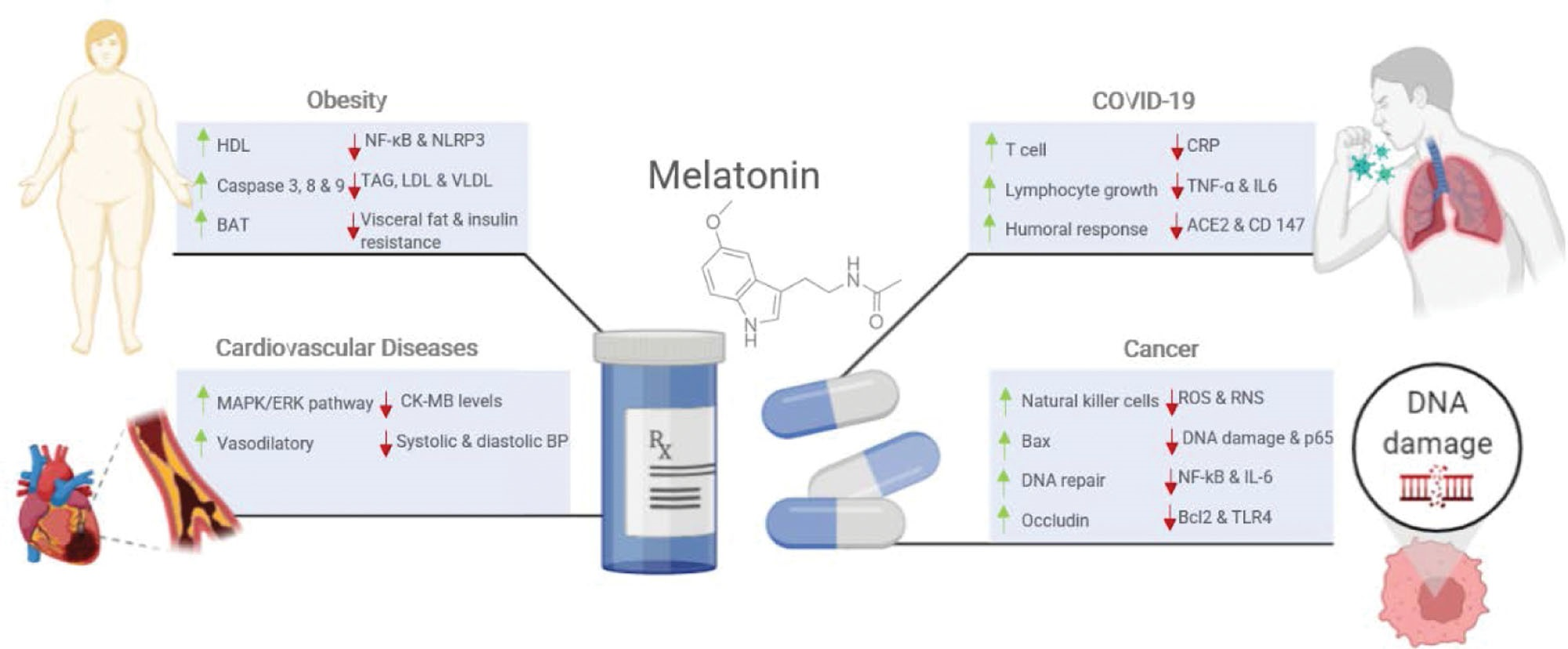

Saudi researchers summarize the potential beneficial mechanisms. Azzeh, Firas S. PhDa,; Kamfar, Waad W. MSca,b; Ghaith, Mazen M. PhDc; Alsafi, Radi T. PhDc; Shamlan, Ghalia PhDd; Ghabashi, Mai A. PhDa; Farrash, Wesam F. PhDc; Alyamani, Reema A. PhDa; Alazzeh, Awfa Y. PhDe; Alkholy, Sarah O. PhDa; Bakr, El-Sayed H. PhDa; Qadhi, Alaa H. PhDa; Arbaeen, Ahmad F. PhDc. Unlocking the health benefits of melatonin supplementation: A promising preventative and therapeutic strategy. Medicine 103(38):p e39657, September 20, 2024. | DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000039657*

The Mechanistic Argument

Here's what proponents of high doses (10-300 mg) are thinking:

Low doses = circadian signaling. At 0.5-5 mg, melatonin primarily works through MT1/MT2 receptors to regulate your sleep-wake cycle. This mimics what your pineal gland does naturally.

High doses = receptor-independent effects. At 10+ mg, you're engaging completely different pathways:

- Direct free radical scavenging: Melatonin and its metabolites neutralize reactive oxygen species. Some studies suggest it's 10x more potent than vitamin E

- Mitochondrial protection: High doses appear to support mitochondrial function and reduce oxidative damage

- Anti-inflammatory cascade: Inhibition of NF-κB, reduction in inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α)

- Potential hormetic effects: Low-level stress that triggers beneficial adaptive responses

The evolutionary argument: Some researchers argue that melatonin's ancient role (it exists in nearly all living organisms, from bacteria to humans) was as a universal antioxidant—not primarily for sleep. They suggest high-dose supplementation is tapping into this deeper, more fundamental protective mechanism.

The Safety Rationale

High-dose advocates point to:

- No established lethal dose in humans

- Decades of off-label use in Europe at high doses without widespread harm reports

- Meta-analyses showing no serious adverse events in short-term high-dose studies (that 2022 Journal of Pineal Research review found risk ratio of 0.88 for serious events with ≥10 mg)

- Successful ICU use at 10-50 mg for conditions like sepsis and delirium

They argue the pharmaceutical establishment is biased toward low doses because that's what the original sleep studies used—not because higher doses are dangerous.

Where the Evidence Is Actually Interesting

I'll be honest: there are specific contexts where high-dose melatonin data is compelling:

Parkinson's Disease:

- Meta-analysis of 7 RCTs (n=245) showed motor score improvements with 10-30 mg

- Proposed mechanisms: mitochondrial protection, reduction of alpha-synuclein aggregation, antioxidant effects in dopaminergic neurons

- Risk-benefit calculation: If you're facing progressive neurodegeneration, a potential 90% increased heart failure risk in 30 years looks very different than if you're 35 and taking it for sleep

Cancer as adjunct therapy:

- 20-40 mg doses alongside chemotherapy reduce side effects (fatigue, neutropenia) with odds ratios around 0.45

- Some studies suggest survival improvements (HR: 0.72 in breast cancer meta-analyses)

- Mechanisms: oncostatic effects, immune modulation, protection of healthy cells from chemo damage

- Risk-benefit calculation: When you're fighting cancer, you're already accepting significant risks from treatment. Adding melatonin may improve quality of life and potentially outcomes

ALS and neurodegenerative conditions:

- Animal models show meaningful delays in disease progression

- Small human trials are ongoing with 50-100 mg doses

- For a condition with limited treatment options and rapid progression, experimental approaches are more justifiable

Metabolic disorders:

- Some evidence for meaningful HbA1c reductions (0.5-0.9%) in type 2 diabetes

- Improvements in insulin sensitivity and endothelial function

- Less clear-cut than the neurological conditions, but showing promise

The Critical Missing Piece

Here's what even the strongest high-dose advocates should acknowledge: We don't have long-term safety data in healthy humans.

Most of this research is:

- Short-term (weeks to a few months)

- In people who already have serious diseases

- Often animal studies extrapolated to humans

- Mechanistically plausible but not proven in rigorous long-term RCTs

And now we have that 2025 preliminary study suggesting cardiovascular risks with prolonged use. Yes, it's observational and may be confounded. But it's also a plausible signal given that:

- Melatonin affects blood pressure regulation

- It influences autonomic nervous system function

- Chronic receptor activation could have downstream effects we don't fully understand

The 2025 Heart Failure Study: What It Means (And Doesn't)

Let's dig into this study since it's driving so much of the current conversation.

What They Actually Found

Study design: Observational cohort of 130,000+ adults with chronic insomnia tracked over 5 years

Findings:

- 90% higher risk of heart failure diagnosis (HR: 1.90)

- 72% higher risk of hospitalization (HR: 1.72)

- 35% higher risk of all-cause mortality (HR: 1.35)

Among people using melatonin for ≥1 year compared to non-users with similar insomnia.

The "It's Just Association" Argument

Critics rightfully point out:

Reverse causation possibility: People with worse underlying health (including early cardiovascular disease) may have more severe insomnia and be more likely to reach for melatonin. The association might reflect who takes melatonin rather than what melatonin does.

Confounding factors: Even with statistical adjustments, observational studies can't fully control for unmeasured variables. Maybe long-term melatonin users have other behavioral or health differences driving the results.

It's preliminary: Not yet peer-reviewed, not published. We need to see the full methodology and data.

Why I'm Not Dismissing It

From a clinical perspective, this signal is worth taking seriously because:

- It's plausible. Melatonin affects cardiovascular function through multiple pathways. Chronic high doses could theoretically have effects on blood pressure regulation, heart rate variability, or vascular function.

- The magnitude is significant. A 90% increased risk (if real) isn't trivial. Even if the true effect is half that after accounting for confounding, it would still be clinically meaningful.

- It aligns with what we're seeing clinically. More patients are taking melatonin for longer periods at higher doses than the original research supported. We need data on what happens with that use pattern.

- The precautionary principle matters. When we're talking about daily use of a hormone for years or decades in otherwise healthy people, "probably safe" isn't the same standard as for a life-threatening condition.

The Balanced View

This study doesn't prove melatonin causes heart failure. But it raises enough concern that:

- We need properly designed long-term RCTs to settle this question

- Higher-risk individuals (older adults, those with existing cardiovascular disease) should be more cautious about prolonged use

- The casual, indefinite use pattern we've fallen into deserves reconsideration

- Risk-benefit calculations need to be individualized rather than treating melatonin as universally benign

.jpg)

The Risk-Benefit Framework: How to Think About Your Situation

This is where we move from "what does the research say?" to "what should I do?"

Scenario 1: You're Using It for Chronic Insomnia

The case against:

- Modest benefits that may diminish over time

- Potential for dose escalation

- Emerging cardiovascular concerns with long-term use

- Better alternatives exist (CBT-I, addressing root causes)

My recommendation:

- Try stopping or tapering (you likely won't have withdrawal, but some people feel temporary sleep disruption)

- Invest in sleep hygiene and CBT-I first

- Reserve melatonin for intermittent use (jet lag, occasional sleep issues)

- If you continue, keep it short-term and low-dose (0.5-3 mg for 2-4 weeks)

Questions to ask yourself:

- Have I actually addressed my sleep hygiene? (Consistent schedule, dark room, cool temperature, no screens 2 hours before bed?)

- Could I have an underlying sleep disorder? (Sleep apnea, restless legs, etc.)

- Am I using melatonin as a crutch to avoid dealing with stress or anxiety?

- Has my dose crept up over time because it's "not working as well"?

Scenario 2: You're Considering High Doses for Anti-Aging/Longevity

The case for:

- Mechanistically interesting for oxidative stress and mitochondrial health

- Some animal data showing lifespan extension

- Relatively low acute toxicity

The case against:

- Very limited long-term human data

- We're seeing potential cardiovascular signals

- Cheaper, better-studied alternatives exist (exercise, Mediterranean diet, other antioxidants)

- You're essentially self-experimenting based on rodent studies

My recommendation:

- Prioritize lifestyle interventions first (they have way more robust longevity data)

- If you want to self-experiment, do it intelligently:

- Start low (even "high dose" advocates suggest building up gradually)

- Track biomarkers (inflammatory markers, lipids, blood pressure)

- Cycle your use rather than daily indefinitely

- Be honest about whether you're seeing benefits

- Consider better-studied alternatives (CoQ10, curcumin, exercise) that don't raise the same cardiac concerns

Questions to ask yourself:

- Am I chasing the anti-aging effect or am I actually just procrastinating on exercise and diet?

- Do I have the health monitoring in place to detect problems early?

- Am I prepared to stop if concerning signals emerge in my own biomarkers?

- What's my actual risk tolerance for an uncertain long-term outcome?

Scenario 3: You Have a Serious Condition (Parkinson's, Cancer, ALS, etc.)

This is where the calculation fundamentally changes.

The case for:

- Limited treatment options for your condition

- Quality of life improvements may be meaningful

- The timeline of your disease may be shorter than the timeline of potential cardiac risk

- You're already managing complex medication regimens with significant side effects

The case against:

- Still limited data even in these populations

- Potential for interactions with other medications

- Individual response varies

- There are more validated medications for this purpose (for example, metformin in cancer - a topic for another day)

My recommendation:

- This is a conversation to have with your oncologist, neurologist, or specialist

- And it is absolutely a great idea to get a second, third, or fourth opinion!

- The risk-benefit calculation is genuinely different when you're dealing with life-threatening or severely debilitating conditions

- Informed self-experimentation makes more sense in this context than for healthy longevity optimization

- Monitor closely for both benefits and side effects

Questions to ask yourself:

- What are my treatment options and how do they compare in terms of side effect profile?

- What's my specialist's perspective on the potential benefits and risks?

- Am I willing to track my response systematically?

- What would I consider meaningful improvement that would justify continuing?

Scenario 4: You're Over 65 with Cardiac Risk Factors

The case against:

- You're in the highest-risk category based on the preliminary 2025 data

- Age-related changes in metabolism mean you clear melatonin more slowly

- You likely have other medications that could interact

- Benefits for sleep may be marginal in your age group

The case for:

- Age-related decline in natural melatonin production might justify replacement

- Some studies show older adults benefit more from slightly higher doses (5 mg vs. 0.5 mg)

- Quality of life impacts of poor sleep are real

My recommendation:

- Be especially conservative about long-term use

- Definitely discuss with your cardiologist if you have any heart history

- If you use it, keep doses low (≤3 mg) and duration limited

- Prioritize alternatives like sleep hygiene, treating sleep apnea if present, addressing medication side effects

Questions to ask yourself:

- Has my doctor evaluated me for sleep apnea or other treatable sleep disorders?

- Are any of my current medications affecting my sleep?

- Would I be willing to try a sleep study or CBT-I before relying on daily melatonin?

- Do I have cardiac risk factors that make me higher-risk for the potential effects seen in that study?

The Alternatives Worth Considering

Whether you're stopping melatonin or just want to optimize your approach, here's what has evidence supporting it:

For Sleep Specifically

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I)

- The gold standard for chronic insomnia

- More effective than melatonin in head-to-head studies

- Benefits persist after treatment ends (unlike stopping melatonin)

- Available through apps, online programs, or in-person therapy

Sleep Hygiene Fundamentals

- Consistent sleep and wake times (even weekends)

- Cool, dark bedroom (65-68°F)

- No screens 2 hours before bed or use blue-light blockers

- Separate wind-down routine

- These aren't sexy, but they work better than any supplement

Magnesium glycinate (if you must try a supplement)

- 200-400 mg before bed

- Helps with muscle relaxation and anxiety

- Generally safe long-term

- Good evidence for improving sleep quality

For Antioxidant/Anti-Inflammatory Effects

If you were taking high-dose melatonin specifically for its non-sleep benefits, consider:

Exercise (seriously, this comes first)

- 30 minutes moderate intensity, 5x/week

- Boosts endogenous antioxidants

- Improves mitochondrial function

- Stronger longevity data than any supplement

- No cardiac risk signals

Curcumin (500-1,000 mg with black pepper)

- Robust anti-inflammatory effects

- Neuroprotective properties

- Cancer-preventive signals

- Generally safe long-term

CoQ10 (100-300 mg ubiquinol form preferred)

- Mitochondrial support

- Cardiovascular benefits (opposite of potential melatonin concerns)

- Good data in Parkinson's

- Safe in older adults

Mediterranean diet pattern

- Perhaps the single strongest dietary intervention for longevity

- Natural polyphenols and antioxidants

- Anti-inflammatory

- Cardiovascular protective

My Personal Synthesis (As Both Physician and Science Communicator)

After spending time with the research and seeing patients navigate this, here's how I think about it:

Melatonin isn't evil, but it's also not a harmless supplement you can take indefinitely without thought.

For acute, short-term situations where circadian timing is genuinely the issue (jet lag, shift work transitions, resetting sleep schedule), low-dose melatonin (0.5-3 mg) makes sense. The data supports it and the risks are minimal.

For chronic daily use in insomnia, I've become increasingly skeptical. The tolerance issue, the dose escalation pattern I see clinically, and now this preliminary cardiac signal make me uncomfortable recommending it as a long-term solution. You're likely better served by addressing root causes and using evidence-based treatments like CBT-I.

For high-dose use in serious disease contexts (Parkinson's, cancer, ALS), I understand why patients and specialists are willing to experiment. The risk-benefit calculation is genuinely different when you're fighting progressive neurodegeneration or cancer. But it should be informed self-experimentation with close monitoring, not casual use based on internet forums.

For healthy longevity optimization, I don't think the current evidence justifies chronic high-dose melatonin when we have so many better-studied alternatives. Exercise, diet, and targeted supplements with cleaner safety profiles make more sense for the vast majority of people.

The theme across all of this: Context matters. Your situation matters. Informed consent matters.

How to Make Your Decision

Here's my framework for thinking through whether melatonin makes sense for you:

Step 1: Define your actual goal

- Better sleep? (Consider: Is it really circadian timing, or something else?)

- Anti-aging/antioxidant effects? (Consider: Are there better alternatives?)

- Support for a specific disease? (Consider: What does your specialist think?)

Step 2: Assess your personal risk

- Age? (>65 = higher concern)

- Cardiac history? (Any heart disease = higher concern)

- How long would you use it? (>6 months = higher concern)

- Current dose? (>5 mg = reconsidering territory)

Step 3: Evaluate alternatives

- Have you actually tried proper sleep hygiene for 4-6 weeks?

- Would CBT-I be appropriate?

- Are there lifestyle changes you're avoiding that would have bigger impact?

- Are there better-studied supplements for your specific goal?

Step 4: If you proceed with melatonin

- Start at the lowest dose that might work (0.1-1 mg)

- Try liquid melatonin or very low tablet doses (harder to find but they do exist!)

- Take it 1-2 hours before desired bedtime, not right before bed

- Set a timeline to reassess (e.g., "I'll try this for 4 weeks and then evaluate")

- If you're not seeing clear benefit, or suffering from side effects like daytime drowsiness, stop

- If your dose keeps creeping up, that's a sign to try something else

- If you're high-risk (older, cardiac issues), discuss with your doctor first

Step 5: Monitor and adjust

- Track your actual sleep quality, not just "am I falling asleep"

- Sleep trackers can be very helpful here

- Pay attention to side effects (even minor ones)

- If you're using high doses, consider monitoring inflammatory markers, blood pressure, lipids

- Be willing to change course if it's not working or if concerns arise

The Bottom Line: It's About Informed Choice

The melatonin conversation is messy right now because we're in this weird in-between space:

- Not enough data to declare it definitively unsafe

- Not enough data to declare long-term high-dose use clearly safe

- Enough mechanistic rationale to keep researchers interested

- Enough preliminary safety signals to warrant caution

I don't think there's one right answer for everyone. That's why I'm not writing this to tell you "never take melatonin" or "high doses are fine."

What I want is for you to make an informed decision based on your specific context:

- Your goals

- Your health status

- Your risk tolerance

- Your understanding of what we know and what we don't

If you have a heart condition and have been taking 10 mg nightly for years because you saw it recommended in a Facebook group? That makes me uncomfortable, and I'd encourage you to talk to your doctor about alternatives.

If you have Parkinson's and you’re working with your neurologist to trial 20 mg to see if it helps with motor symptoms? That's a different calculation, and I understand the reasoning.

If you're 35 taking 0.5 mg occasionally for jet lag? That seems very low-risk and exceptionally reasonable based on current evidence.

If you're 40 taking 15 mg every night for "longevity" without monitoring and while neglecting exercise and diet? I'd encourage you to rethink your priorities and approach.

Know thyself. Know the evidence. Make your decision accordingly.

And stay tuned—because this is one area where our understanding is genuinely evolving, and I expect we'll have better data in the next few years to guide these choices with more confidence.

What's your take? Are you reconsidering your melatonin use, or does your situation make it worth continuing? I'd love to hear your perspective—hit reply and let me know what you're thinking.

Hillary Lin, MD

P.S. - If you found this deep dive helpful, forward it to someone who's been asking about melatonin. And if someone forwarded this to you, you can subscribe to The Longevity Letter for evidence-based breakdowns of confusing health topics.

References

- American Heart Association. Long-term use of melatonin supplements to support sleep may have negative health effects. Published November 3, 2025. Accessed November 6, 2025. https://newsroom.heart.org/news/long-term-use-of-melatonin-supplements-to-support-sleep-may-have-negative-health-effects.

- Azzeh FS, Kamfar WW, Ghaith MM, Alsafi RT, Shamlan G, Ghabashi MA, Farrash WF, Alyamani RA, Alazzeh AY, Alkholy SO, Bakr EH, Qadhi AH, Arbaeen AF. Unlocking the health benefits of melatonin supplementation: A promising preventative and therapeutic strategy. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024 Sep 20;103(38):e39657. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000039657. PMID: 39312371; PMCID: PMC11419438.

- Badran AS, Khelifa H, Gbreel MI. Exploring the role of melatonin in managing sleep and motor symptoms in Parkinson's disease: a pooled analysis of double-blinded randomized controlled trials. Neurol Sci. 2025 Sep;46(9):4155-4168. doi: 10.1007/s10072-025-08221-8. Epub 2025 May 19. PMID: 40387966; PMCID: PMC12394315.

- Bald EM, Nance CS, Schultz JL. Melatonin may slow disease progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Findings from the Pooled Resource Open-Access ALS Clinic Trials database. Muscle Nerve. 2021 Apr;63(4):572-576. doi: 10.1002/mus.27168. Epub 2021 Jan 24. PMID: 33428242; PMCID: PMC8842494.

- Butler M, D'Angelo S, Perrin A, Rodillas J, Miller D, Arader L, Chandereng T, Cheung YK, Shechter A, Davidson KW. A Series of Remote Melatonin Supplement Interventions for Poor Sleep: Protocol for a Feasibility Pilot Study for a Series of Personalized (N-of-1) Trials. JMIR Res Protoc. 2023 Aug 3;12:e45313. doi: 10.2196/45313. PMID: 37535419; PMCID: PMC10436115.

- Delpino FM, Figueiredo LM, Nunes BP. Effects of melatonin supplementation on diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clin Nutr. 2021 Jul;40(7):4595-4605. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2021.06.007. Epub 2021 Jun 16. PMID: 34229264.

- Fatemeh G, Sajjad M, Niloufar R, Neda S, Leila S, Khadijeh M. Effect of melatonin supplementation on sleep quality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Neurol. 2022 Jan;269(1):205-216. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-10381-w. Epub 2021 Jan 8. PMID: 33417003.

- Ferracioli-Oda E, Qawasmi A, Bloch MH. Meta-analysis: melatonin for the treatment of primary sleep disorders. PLoS One. 2013 May 17;8(5):e63773. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063773. PMID: 23691095; PMCID: PMC3656905.

- Iftikhar S, Sameer HM, Zainab. Significant potential of melatonin therapy in Parkinson's disease - a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Neurol. 2023 Oct 10;14:1265789. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1265789. PMID: 37881313; PMCID: PMC10597669.

- Jacob S, Poeggeler B, Weishaupt JH, Sirén AL, Hardeland R, Bähr M, Ehrenreich H. Melatonin as a candidate compound for neuroprotection in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): high tolerability of daily oral melatonin administration in ALS patients. J Pineal Res. 2002 Oct;33(3):186-7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079x.2002.02943.x. PMID: 12220335.

- Lv X, Sun H, Ai S, Zhang D, Lu H. The effect of melatonin supplementation on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2025 Jul 8;16:1572613. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2025.1572613. PMID: 40698248; PMCID: PMC12279524.

- Menczel Schrire Z, Phillips CL, Chapman JL, Duffy SL, Wong G, D'Rozario AL, Comas M, Raisin I, Saini B, Gordon CJ, McKinnon AC, Naismith SL, Marshall NS, Grunstein RR, Hoyos CM. Safety of higher doses of melatonin in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pineal Res. 2022 Mar;72(2):e12782. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12782. Epub 2021 Dec 30. PMID: 34923676.

- Posadzki PP, Bajpai R, Kyaw BM, Roberts NJ, Brzezinski A, Christopoulos GI, Divakar U, Bajpai S, Soljak M, Dunleavy G, Jarbrink K, Nang EEK, Soh CK, Car J. Melatonin and health: an umbrella review of health outcomes and biological mechanisms of action. BMC Med. 2018 Feb 5;16(1):18. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-1000-8. PMID: 29397794; PMCID: PMC5798185.

- Yousef O, Abouelmagd ME, Khaddam H, Shbani A, Yousef R, Meshref M, Hanafi I. The Effectiveness of Melatonin for Sleep Disturbances in Parkinson' Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Sleep Res. 2025 Jun 30:e70097. doi: 10.1111/jsr.70097. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40588412.

.jpg)

.jpg)